In the early 1960s, Mexico’s industrial landscape was undergoing a transformation. Under the protective shadow of import-substitution policies championed by President Miguel Alemán Valdés, borders were closed to foreign goods to nurture domestic manufacturing and reduce reliance on imports.

It was against this backdrop that a group of industrialists, led by the German-Mexican Hessel brothers—Carlos, José, and Luis—saw an opportunity to expand beyond their established metal products ventures. Their flagship company, Acermex, had spent nearly two decades building a powerhouse in bicycle production. The company churned out hundreds of thousands of frames and components annually from a factory complex outside Mexico City.

Encouraged by that success, the brothers, along with key executives Pablo Tortoriello and Italian expatriate Remo Vecchi, set their sights on motorcycles. There was a burgeoning market fueled by post-war mobility demands and the allure of affordable personal transport. Carabela Motorcycles traces directly to this ambition.

In 1964, Acermex launched Carabela as a dedicated motorcycle division in Naucalpan, just outside of Mexico City. The name Carabela means caravel in English—a small, highly maneuverable sailing ship developed in the 15th century by the Portuguese and widely used by both Portuguese and Spanish explorers during the Age of Discovery.

Tortoriello, as general director, spearheaded the venture, while Vecchi traveled to Italy to secure engines that could power Mexican-designed frames. The partnership with Minarelli, a successful Italian manufacturer specializing in lightweight two-stroke engines, became the cornerstone of Carabela’s rise.

The first shipment from Minarelli was a collection of 50cc and 100cc two-strokes. However, a chassis needed to be developed and manufactured. Specialized manufacturing machinery poured in from Italy, Germany, and Czechoslovakia, alongside a cadre of engineers from Europe, the United States, and Asia. Acermex’s existing steel tubing production line adapted quickly and was fabricating frames in-house.

Initially, Carabela focused on local needs, assembling mopeds and small-displacement bikes for city commuters and rural workers. Early models were utilitarian, with minimal frills. Carburetors and electrical components remained imported, though Mexican welders and assemblers soon handled heads, covers, and other castings. By 1966, production ramped up to include 66cc, 125cc, 175cc, and 200cc variants, all two-strokes for their simplicity and low cost.

These formative years were marked by trial and error. Early Carabelas suffered from fragile frames that cracked under stress—a common pitfall for newcomers. A 175cc model emerged as an early standout, with a single downtube frame, suspended by twin shocks and an Earles-style fork, and a top speed near 70 mph.

Priced affordably for Mexican buyers, the 175 found favor among urban riders seeking a budget alternative for daily duties. By the late 1960s, Carabela motorcycles had created a budding sense of rider camaraderie. Annual output climbed, and the brand’s reputation solidified as a homegrown success story.

A turning point came in 1969. Carabela ventured into off-road territory with the launch of its first motocross bike—the 125 Caliente. It was Mexico’s inaugural foray into competitive dirt machinery, designed to challenge the dominance of Japanese and European imports in the growing sport of motocross.

The Caliente’s two-stroke Minarelli engine displaced 125cc and was fed by a 27mm Dell’Orto carburetor, delivering competitive power matched to a five-speed gearbox. Weighing just under 200 pounds dry, it featured a lightweight chromoly frame, Betor fork, and Boge shocks—components sourced from Italy for proven durability. Barnum knobbies were mounted on the requisite 21-/18-inch wheelset.

Contemporary reviews were mixed regarding the Caliente’s potential. Cycle World called it “light, well-finished, and capable of winning,” noting its surprising acceleration and excellent handling in tight turns. Cycle Guide echoed this, highlighting how the bike’s power rivaled pricier imports, though it demanded careful break-in to avoid seizing the motor. Dirt Bike magazine’s enthusiasm was tempered by the odd engineering, inconsistent quality control, and lack of reliability. Still, Dirt Bike allowed that the Caliente was “peppy for its size.”

At $795, the Carabela 125 Caliente’s price undercut many rivals, making it accessible for amateur racers. The red livery earned it the “hot” moniker, and it quickly appeared at Mexican scrambles. The Caliente represented a hometown breakthrough—a Mexican bike that could hold its own against global heavyweights.

Building on this momentum, Carabela expanded its motocross lineup in 1971 with the 125 MX, a refined evolution of the Caliente, built explicitly for the US market, where demand for affordable 125cc racers was surging. This model addressed early critiques by improving frame geometry for better stability, increasing suspension travel slightly, and porting the Minarelli engine to focus on mid-range punch. The bike weighed 186 pounds dry, with agility emphasized over brute force.

By the mid-1970s, the factory employed over 3,000 workers and produced 300,000 bicycles and motorcycles annually. Exports to the US grew, with the Caliente, 125 MX, and Marquesa gaining niche followings among budget-conscious riders.

The 1975 Carabella 125 Marquesa marked the pinnacle of Carabela’s motocross era. Named after a storied Mexican coin, the Marquesa borrowed aesthetics from the Honda Elsinore 125. It featured sleek lines, a fiberglass tank, and a riding position that favored aggressive cornering. Popular Cycling noted its “remarkable resemblance to an Elsinore,” but with Mexican engineering tweaks.

Powered by the familiar Minarelli 125cc motor, it produced around 18 horsepower to propel the 198-pound bike. The Betor fork offered seven inches of travel, and the long-travel suspension revolution was getting underway, though the Boge shocks were still in the short-travel era.

Priced at $899, the Marquesa appealed to weekend warriors and club racers. In the US, it saw limited but dedicated use. Dirt Bike West sponsored riders in Southern California events, where the bike shone in desert terrain.

Yet, even as motocross models like the Marquesa turned heads, storm clouds gathered. The oil crises of the 1970s inflated raw material costs and the price of imported components. At the same time, the Japanese giants flooded markets with reliable, mass-produced alternatives, eroding Carabela’s affordability edge.

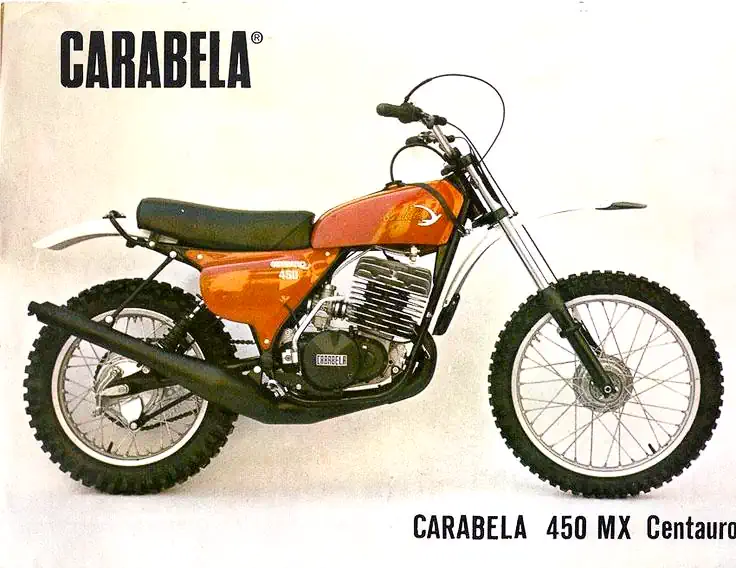

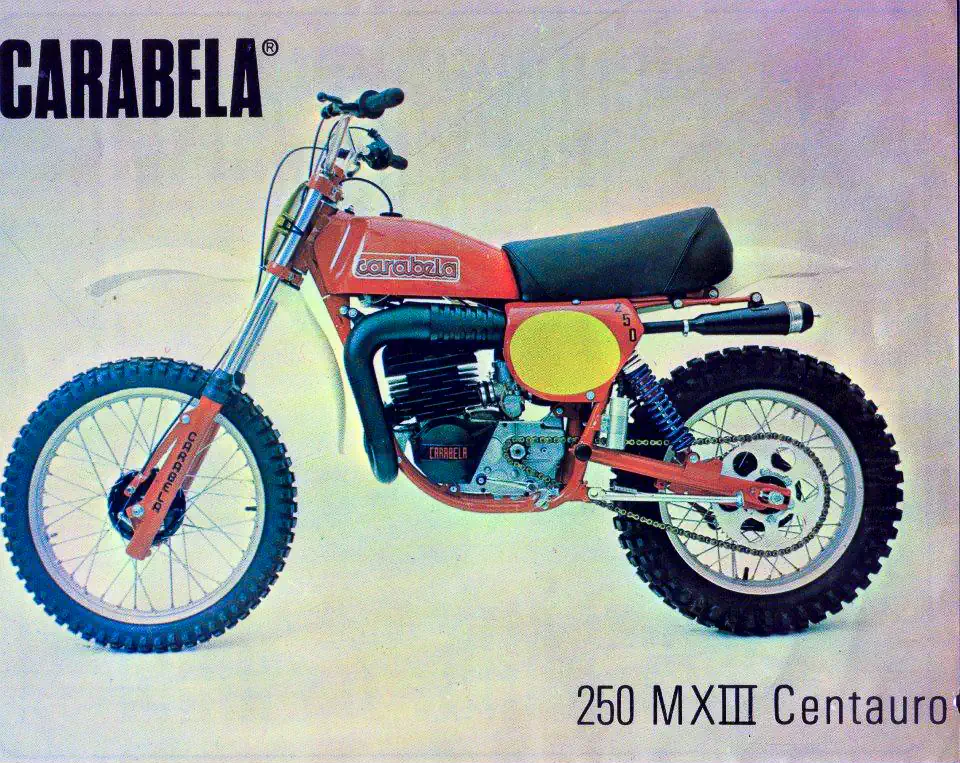

Carabela’s international ties were integral to its motocross success. Beyond Minarelli’s engines, partnerships with Villa provided robust powerplants for larger models like the Centauro 250 and 360cc two-strokes, which incorporated more Italian DNA, including whole bikes from Moto Villa. Components from Betor, Ceriani, and Boge reassured buyers.

By 1978, the cracks were forming. The high-strung engines in Carabela racers required meticulous tuning and maintenance to compete, deterring casual users who had many other, more reliable options.

The fatal blow to Carabela was landed in the late 1980s. In a bid for scale, Carabela was acquired by the Monterrey-based Grupo Alfa, a conglomerate with interests in petrochemicals and finance. Alfa expanded administrative ranks, bloating the overhead. Production costs soared as labor and management expenses rose, forcing price hikes. Sales plummeted, as prices increased by 50 percent.

By 1987, motorcycle assembly ended amid mounting losses. Parts production limped on until 1990, when Carabela filed for bankruptcy in the early 1990s.

The demise stemmed from a perfect storm of mismanagement under new ownership, intensified global competition, and failure to innovate. Alfa’s institutionalization, while aiming for efficiency, instead diluted the brand’s unique appeal.

Moto Road S.A. de C.V. acquired the Carabela brand name in 2001. Reborn with Chinese components, it offers basic motorcycles, scooters, and ATVs—something of a return to the brand’s roots of affordable transportation, though without the Hecho en México cache.

For vintage enthusiasts, however, the 1970s Carabela motocrossers are cult machines. Restored Calientes and Marquesas still rip through AHRMA events and can evoke five-figure bids at Mecum Auctions. Carabela serves as a reminder of Mexico’s la época dorada, when underdogs dared to race with the giants.